Setting History Straight

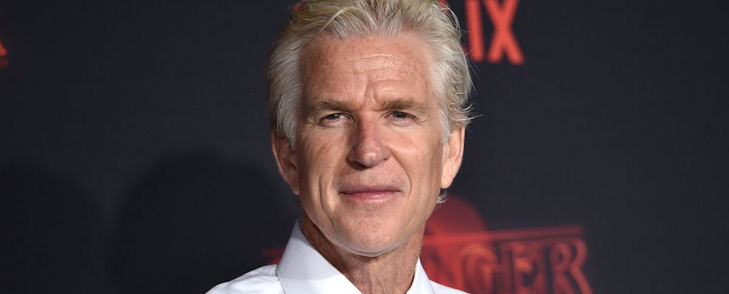

When actor Michael Biehn answered a knock at the door of his Chelsea residence one bitter cold September morning in 1985, he found a shivering, shoeless man. Strikingly good looking and cheerful, the man introduced himself. “Hi, I’m Tim Colceri. I’m living in your basement.” Biehn was staying in the comfortable London house while performing the iconic role of Sgt Hicks in Aliens, re-teaming with his Terminator director Jim Cameron. Colceri, also an actor, was staying in the separate basement apartment as he rehearsed for the role of Sgt Hartman, the hard-ass drill instructor in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. When Biehn showed him in, Colceri asked if Biehn and his wife were hungry. He proceeded to make a full English breakfast while barking out with obvious pride the dialogue he’d been relentlessly rehearsing. When he left a few hours later, Biehn and his wife looked at each other.

“That guy is going to be a star,” Biehn said to her.

Little could anyone appreciate that day that instead of acting in Stanley Kubrick’s next movie, Colceri would soon be living out Kubrick’s horror film, The Shining. Or that the grueling, repetitive torment to which Kubrick would put that naive, eager young actor, who lacked an agent shielding him, would be mirrored in the Drill Instructor’s treatment of Pvt. Pyle Kubrick displayed on screen in Full Metal Jacket. Needing an overcoat for the bracing British weather, Biehn set out for nearby King’s Road. Colceri accompanied him and while Biehn looked at coats, Colceri slipped into an off-track betting parlor. An avid handicapper, his four pound trifecta ticket returned twenty-four hundred. “I’m paying for that,” he declared when he saw Biehn had selected a three hundred pound garment. He tossed in a snappy Fedora and asked the salesman for the name of the best steakhouse in London.

“I thought then that he was as big-hearted as he was talented,” Biehn remembers.

With only Saturday available for nightlife, they headed for Stringfellow’s, London’s trendiest club, and took a position at the end of a very long line. After only a few minutes, Colceri wandered away. When he returned, he took Biehn directly to the door. “Michael, this is Peter Stringfellow. I was just talking and he said ‘Give this guy a lifetime membership.” As he led them in, Stringfellow said to Biehn “Can’t wait to see your friend onscreen.” Biehn had been around outsized personalities in Hollywood, people like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Mel Gibson, figures who energize and command every room they enter. His dear friend Bill Paxton, also in London for Aliens, was all of that, too. But Colceri simply wowed him.

* * *

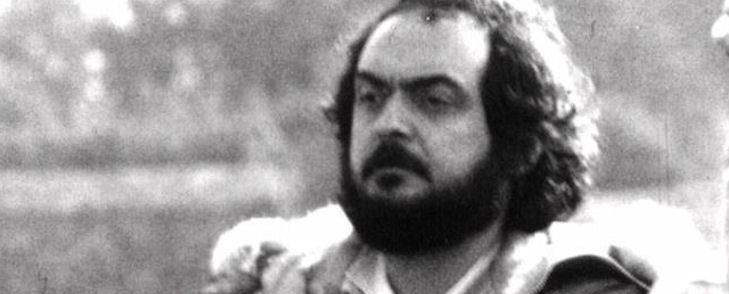

Colceri’s very presence in London was the stuff of Hollywood mythology. Just a few months earlier, he’d been an aspiring actor in Los Angeles with a few commercial credits when one day his phone rang. “Tim, this is Louis Blau calling on behalf of Stanley Kubrick. Tim, I have a great deal of faith in Stanley Kubrick. Stanley Kubrick has a great deal of faith in Tim Colceri. Come to my office and sign your contract.” Colceri had long forgotten about the videotape of himself posing as a Marine drill instructor he’d sent to England three years earlier when he heard that the travel-averse filmmaking legend would be shooting a movie following Marines through boot camp and on to Vietnam. Having been a Marine who served in Vietnam, Colceri got another “jarhead” to pose as a hapless recruit while he portrayed a drill instructor. Blau’s spacious Century City office overlooked the Los Angeles Country Club and when Colceri commented what a great golf course it was thought to be, Blau told him “You sign a few more of these contracts and you can play that course anytime you want.” Blau opened his desk drawer and pulled out a screenplay. “I think you have the finest role in the film. You play the Drill Instructor.” Eight weeks later Colceri was in London eager to begin rehearsals.

Colceri was met at the airport by a driver with a note: “Learn pages 1-28 by tomorrow morning. Driver will pick you up at 7. Stanley.” Too eager and naive; too much the obedient Marine who snaps to attention, salutes, and barks out “Yes, sir!; Colceri did not realize just how peculiar and unsettling that note was. Those pages largely consist of one intense, extended monologue of the hard-assed Drill Instructor berating his recruits. There’s no real purpose to be gained in expecting an actor to have that much material ready before even meeting the director or anyone else he needs to see upon arrival. For that matter, this acting job had been unusual from the start. Most actors would have received an offer through an agent; if the actor is unrepresented, the company would likely have helped find one if only for their own convenience and protection.

Colceri spoke with Kubrick only briefly on their first meeting. “Mr. Kubrick, if you ask me for a thousand takes, I’m prepared to give you a thousand and one,” he enthused. “Ah, don’t believe the propaganda,” Kubrick told him. With that, Colceri went off to begin rehearsing with Leon Vitali, Kubrick’s indispensable factotum who had forsaken his own acting career to serve Kubrick’s every need after appearing in Barry Lyndon. Kubrick’s schedule called for shooting the Vietnam sequences first so Kubrick could then record the actors getting their heads shaved. Colceri’s work with these actors was still weeks away and on the dubious notion that separating the Drill Instructor and the recruits would result in more “authentic” performances, Kubrick isolated Colceri from the rest of the cast and crew.

A grueling six day-a-week, twelve hour-a-day routine quickly ensued. Working with only Vitali, Colceri rehearsed scenes throughout the day; Vitali nightly took the tapes to Kubrick. Vitali allowed no deviation from the words on the page, although the pages changed endlessly. Rehearsing what was to be the opening of the film (the Drill Instructor addressing the recruits prior to their haircuts), Vitali interrupted when Tim left out the word “down” when ordering them to sit. Colceri vented himself on a chair and then did a reading in which he roared out the word “DOWN!!” Vitali put his arm around Tim. “Stanley’s going to be so proud, he just wanted to see that you could handle your lines every different way. It took Scatman Crothers 122 takes to get the pantry scene in The Shining. We had to break into his hotel room and pull him out from behind the curtains.”

Almost as soon as Colceri got to London, Kubrick overwhelmed him with work and alienated him from the others with whom he was supposed to be making a film. The character of the Drill Instructor operates at such an extreme level of intensity that even just rehearsing the part so incessantly becomes enervating and numbing. What makes it many times worse for actors is to be told they will be shooting and then undergo the exhaustive “gearing up” required only to be told “No, we’re not shooting today, after all.”

“When I know I’m going to be shooting an intense scene the next day,” Biehn observes, “that becomes my complete focus until the camera rolls. It’s what we live for as actors, it’s exhilarating, but exhausting.”

Enthusiastic by nature, and eager to be performing at last, Colceri was especially excited the first time he was told he’d be shooting. But the day came and went without another word. And that wouldn’t be the only occasion; Biehn recalls with growing alarm helping Colceri prepare for shooting the next day only to be told it didn’t happen as October dragged into November.

As much as Colceri may have been kept estranged from the Full Metal Jacket set, he was embraced by all at the Aliens set during the half dozen times he visited. “They treated me like I was one of them. Usually when he saw me, Jim Cameron would say ‘Hey, Colceri, come take a look at this cool thing we’re going to do.” He rode to the Aliens cast and crew Thanksgiving dinner with Biehn and Sigourney Weaver and still counts Biehn and Aliens cast member Mark Rolston among his closest friends. And Colceri muses now that he actually spent more time with Cameron than he did with his own director. As Aliens neared wrap, Biehn prepared to leave shortly before Christmas. Full Metal Jacket was then wrapping just it’s Vietnam sequences. That meant Colceri, after ten weeks of enervating daily rehearsals, would finally be shooting. Then, on a Sunday, as Biehn and Colceri were sitting in his front room, Leon Vitali pulled up in his high end car and exited with a letter in his hand. “Is he taking my role away?” Colceri asked after opening the door. “Read the letter.”

Kubrick

wrote that he was being replaced by technical

adviser Lee Ermey,

who had once been a drill

instructor.

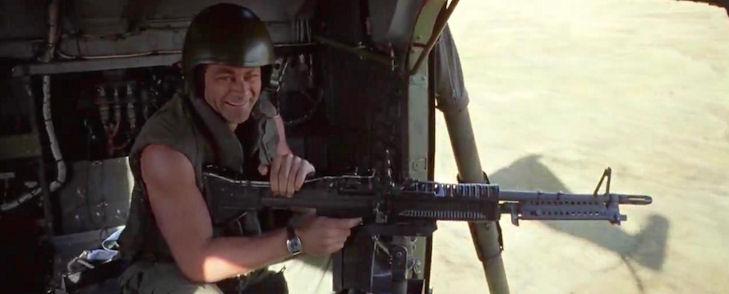

Kubrick offered Colceri a part as a helicopter door

gunner. The character’s dialogue fit on one page.

In later interviews,

Ermey talks about how he

maneuvered to get the part, pouring it on when he

knew Leon was taping his work with extras to show

Stanley.

No purpose had been served by keeping

Colceri away from the cast and crew.

Crestfallen, Colceri departed for his basement. “I

feel bad about . . .” Vitali started to say before

Biehn cut him off. “You have three seconds to get

out of my house.” Only when Biehn started to count

did Vitali bolt for his car.

If Colceri thought that

being fucked with by Stanley was finally over, he

couldn’t have been more wrong. It

only intensified. He’d been rehearsing the new part

for less than a week when Leon called. Ermey had

almost killed himself driving into a tree. Once

again, Colceri would be playing the Drill

Instructor. His spirits soaring, Colceri told people

that he’d been destined to play the role. Until a

few days later, when

Leon informed him that the production would

shut down to await Ermey’s recovery months down the

road. Once again, Kubrick had dashed Colceri’s

hopes.

Colceri had been back in Los Angeles for six months before getting word that shooting would resume. He started rehearsing for his brief, manic moment onscreen as the Door Gunner. Then his agents (he was now with Biehn’s ICM representatives) called with news that the character was now dropped from the film. “I went from having the major role in a Stanley Kubrick movie to having nothing whatsoever.” Losing the Drill Instructor role as he did was horrifying enough — and now, this. Ed Limato, Biehn’s long time agent whose stellar client roster included Warner Brothers franchise linchpin Mel Gibson, picked up the phone. Some accounts have the word “lawsuit” being uttered and suddenly the Door Gunner was back in the picture. The night before he was to shoot at last, Colceri ventured out to Kubrick’s country estate. They sat in the helicopter parked in Kubrick’s courtyard and went over his lines. Kubrick stepped into his office and started typing dialogue, inserting the paper horizontally, just like the letter Leon delivered. Colceri finally got to work the next day. Kubrick arrived after ten rehearsals had been filmed and viewed the results. “Lose the laugh, just give me that everyday killer Marine look,” Kubrick instructed him, “Now go back up there and do it fifteen more times.” Vietnam vet Colceri never has figured out what an “everyday killer Marine look” is and after the movie’s release, he saw that in the editing room, Kubrick used the take with Colceri’s laughter.

* * *

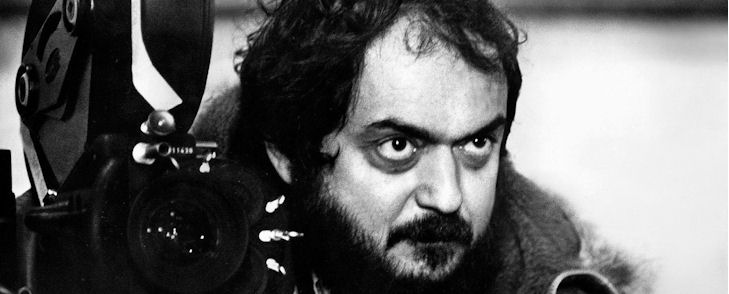

London that fall of 1985 had to have been an enthralling time for Biehn and Colceri, young actors early in their careers working hard now on major films by directors certain to be among the handful of the art form’s greatest. Their experiences — Biehn’s with Cameron and Colceri’s with Kubrick — becomes a study in contrasts that leads to a fuller, more unblinking appraisal of the price paid by those who worked for Kubrick, who was, in turn, oblivious and indifferent. With his later films, Kubrick operated with a degree of independence and autonomy few directors attain. Did that latitude result in better movies? At what cost?

Colceri appeared in television and movie roles in the years following Full Metal Jacket and now resides in Las Vegas. Ever the Marine and buoyant by nature, he is proud to have played the Door Gunner, and he played the hell out of it. He doesn’t permit himself to ponder for too long the “what if?” question. People often recognize him and when asked if he was in Full Metal Jacket, Colceri proudly replies “Yeah, I played the Door Gunner!’” But one can’t help but wonder how things might have gone for Colceri had Kubrick stuck with him. The part was a career maker.

Fans tell Biehn frequently “No one but you could have played Kyle Reese (Terminator) or Johnny Ringo (“Tombstone).” Biehn knows better. “A number of other actors could have taken those roles and brought their own talents to them — those were just great roles. Everybody identifies Lee Ermey with that Drill Instructor but I saw a better, richer performance, more intimidating and intense.”

Was any of it necessary? To begin intensive rehearsals months before photography, to be told repeatedly he would be performing, only to pull it away every time until they pulled that away for good? If Kubrick had designed a torment for Colceri, it’s hard to think of a worse one than this. Derek Cracknell, Kubrick’s first assistant director on The Shining, talks in one documentary about how he and Kubrick deliberately tormented Shelley Duvall so she’d appear terrified onscreen. The Netflix documentary Filmworker covers Leon Vitali’s years working for Kubrick. “He sucked the life out of you,” Vitali assesses of the man to whom he devoted twenty years of his life. “If you told Stanley you’d give your right arm to work for him, he’d think you were lowballing him. He’d want your left and everything else.”

The gulf between Dr. Strangelove, his tight,

purposeful masterpiece, and Eyes Wide Shut, which

can only be endured that way, argues that

free reign for

Kubrick didn’t produce better movies; they only got

worse. And it took a real toll on

the lives of real people who craved to be a part of

the life of a filmmaking legend who found them all

utterly dispensable once they’d served his purpose.

* * *

I didn’t set out to write the above. It grew out of a shard of a memory, long cached away in some cerebral recess, sparked to life when I talked to Tim Colceri for the first time in nearly thirty years. I met Tim when Full Metal Jacket was in the theaters and thoroughly enjoyed the few occasions we were together, but our paths diverged soon after that.

So I was thrilled to talk to Tim recently. Once again, Michael was the link; he’d visited Tim in Las Vegas where Tim had moved seven years earlier. I remembered the basic facts of Tim’s time in London; he’d gone there to play the Drill Instructor but instead had wound up being the Door Gunner who memorably proclaimed that it’s easy to shoot women and children, you just don’t lead them as much, something a real door gunner had informed writer Michael Herr. Beyond that I knew little. But as we spoke again, and as I heard more from Biehn of what he recalled, a narrative began to emerge that I wanted to pursue. I got more detail from both and watched Filmworker on Netflix, Leon Vitali’s “vacant stare” look back at his twenty years working with Kubrick. Five minutes of the film revolve around these events, and bile rose in my mouth as Vitali talked about dreading making that drive to Colceri’s house, knowing at the other end were two people I know and one of them was about to be delivered a soul crushing blow.

As the narrative came together, I realized just how insidiously, callously foul Kubrick had treated Tim. And Tim was by no means alone. This new perspective on Kubrick the man, dealing with the people who put themselves forward to serve him, made the cold and antiseptic aura of his films make a crude sense. As he acquired more authority, as people extended themselves for him, he was able to withdraw into his own domain, freed from the chore of actually having to deal with people, and his movies became as cold and distant as their maker.

I showed this piece to Michael for comment on accuracy and completeness. “The details are all there, Jim,” Michael said, “but they don’t convey the true dimension of that nightmare. I know great filmmakers revere him; Cameron, Spielberg, Scorsese all said he inspired them, but they didn’t have to work for him. I don’t see it. His movies just got more awful after Strangelove until he wound up with that final abomination. And as a man, he was a soulless monster. It’s not that he didn’t care what he did to you, he wasn’t even aware of you. A bully, a liar, a tyrant. If you look up the word “sociopath” in the dictionary . . . I think it fits him perfectly.”

By Michael Biehn & Jim Anderson

Tim Colceri - official website