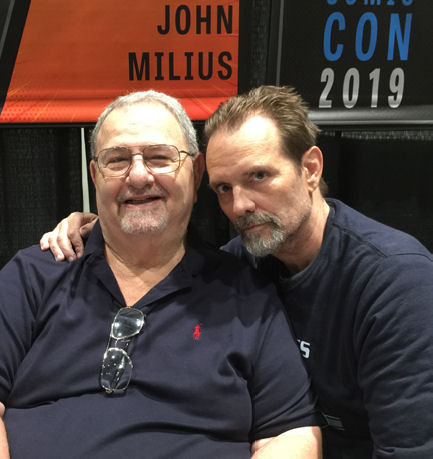

Mention of the name “John Milius” invariably brings a smile to anyone involved in show business who knows anything of the man, and that’s been true from the start of his career. Folks swap stories of his delightful eccentricities, always backed with a fierce admiration for his audacious talent and bravura personality. That was certainly the case in the unique perspective of “Miliusworld” I, Jim Anderson, enjoyed in the late 1970s while servicing Field Marshal Milius.

“Servicing” has a particular meaning in the talent agency business, and no, don’t let your imagination go to the obvious innuendo. (Although that, too, happens; Reese Witherspoon married one of her CAA agents, Jim Toth.) In agency lingo, “servicing” a client refers to performing the regular tasks of representation: soliciting employment; submitting client materials (e.g., films and screenplays); negotiating deals; chasing down money owed for services provided; and otherwise addressing a client’s concerns (that last task sometimes known as “lip- servicing”).

Each

artist presents a unique set of “servicing”

requirements, and that was never truer than with

Milius. He was a client of the agency where I got my

start in the mail room, International Creative

Management in the late 1970s, and specifically of

the agent under whom I apprenticed, Jeff Berg. Berg

became president of the agency while I worked for

him, and he chaired the company for nearly 30 years.

Our clientele included many of the “Easy

Riders and Raging Bulls” legends: Steven Spielberg,

George Lucas, Peter Bogdanovich, Brian de Palma,

Paul Schrader and, of course, Field Marshal Milius.

Further, my roommate at the time, actor/ writer

Darrell Fetty, had appeared in a sizable role in Big

Wednesday and was just exiting a marriage to Milius’

executive assistant; he was very much a part of

Miliusworld.*

Each

artist presents a unique set of “servicing”

requirements, and that was never truer than with

Milius. He was a client of the agency where I got my

start in the mail room, International Creative

Management in the late 1970s, and specifically of

the agent under whom I apprenticed, Jeff Berg. Berg

became president of the agency while I worked for

him, and he chaired the company for nearly 30 years.

Our clientele included many of the “Easy

Riders and Raging Bulls” legends: Steven Spielberg,

George Lucas, Peter Bogdanovich, Brian de Palma,

Paul Schrader and, of course, Field Marshal Milius.

Further, my roommate at the time, actor/ writer

Darrell Fetty, had appeared in a sizable role in Big

Wednesday and was just exiting a marriage to Milius’

executive assistant; he was very much a part of

Miliusworld.*Milius has talked about being a frustrated Marine; he was denied enlistment during the Vietnam War because of severe and chronic asthma. As was so true of John the contrarian, this was at a time when most of his contemporaries finagled ways to avoid military service. But his infatuation with the military never left him and penetrated his work and demeanor. He named his company “A Team Productions” (I’ve always felt Stephen J. Cannell owed Milius a royalty for his TV series of the same name, as that’s clearly where he got it). His letters and memos frequently reflected a militaristic swagger, and he was fond of signing them with the affectation “Field Marshal Milius.”

A lot of this attitude was Milius showing his disdain for liberal-leaning Hollywood’s “political correctness” before anybody was using the term. But not all of it: What he saw as the warrior’s ethos is very much on display in his work. In Hollywood, Milius is as much admired for his contributions to movies for which he received no credit as he is for those for which he did. He infused Clint Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” with the taunts that would become the series’ signature lines: “Go ahead, make my day,” “You’ve got to ask yourself a question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do ya, punk?” He wrote Robert Shaw’s riveting “sinking of the Indianapolis” monologue for Jaws and suggested to his pal Steven the Normandy Graveyard scenes that bookend Saving Private Ryan.

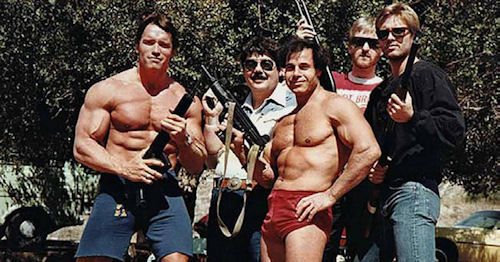

Milius’s

fondness for all things military wasn’t confined to

his work but was a vital component of his deal

making as well. Contracts for his services included

a clause that I never saw in any other client’s

agreements — that his compensation had to include a

firearm of his choosing. And Milius was very adept

in their use. Michael Biehn fondly remembers an

afternoon he spent with Milius, Jim Cameron, Arnold

Schwarzenegger, and champion body builder/Strongman

Franco Columbu shooting all manner of weaponry.

Arnold and Franco had known each other for years;

Franco appeared in Conan and would play the

Terminator from the future. Principal photography on

The Terminator was only a month away when Milius had

to contact Jim Cameron with bad news: Arnold’s

option for a Conan sequel was being exercised and

Terminator would have to wait. To make amends he

suggested they all head for the countryside and

shoot stuff up with Milius’s arsenal. Each of these

fellows was a dominating figure in his own right,

but Michael was awed by how much “larger than life”

Milius seemed, even around these guys. Gregarious

and chomping on a cigar, Milius was intimately

familiar with the specifications and performance

capabilities of each firearm and everyone deferred

to him.

Milius’s

fondness for all things military wasn’t confined to

his work but was a vital component of his deal

making as well. Contracts for his services included

a clause that I never saw in any other client’s

agreements — that his compensation had to include a

firearm of his choosing. And Milius was very adept

in their use. Michael Biehn fondly remembers an

afternoon he spent with Milius, Jim Cameron, Arnold

Schwarzenegger, and champion body builder/Strongman

Franco Columbu shooting all manner of weaponry.

Arnold and Franco had known each other for years;

Franco appeared in Conan and would play the

Terminator from the future. Principal photography on

The Terminator was only a month away when Milius had

to contact Jim Cameron with bad news: Arnold’s

option for a Conan sequel was being exercised and

Terminator would have to wait. To make amends he

suggested they all head for the countryside and

shoot stuff up with Milius’s arsenal. Each of these

fellows was a dominating figure in his own right,

but Michael was awed by how much “larger than life”

Milius seemed, even around these guys. Gregarious

and chomping on a cigar, Milius was intimately

familiar with the specifications and performance

capabilities of each firearm and everyone deferred

to him. Despite the swagger, Milius was a pussycat as a client — largely, I suspect, because he didn’t expect much from his agents. To be fair, he didn’t expect much of people in general, preferring to rely on himself and his talents. His services were always in demand, so he never chafed at not working and he learned long ago that agents aren’t miracle workers. In interviews, he expressed fondness for his first agent, Mike Medavoy.

“I worked all the time with Mike representing me. I never made any money, but I was always busy,” Milius recalled. Medavoy began his career at one of ICM’s predecessor companies, and Milius stayed with the agency when Medavoy departed to run United Artists and later Orion Pictures.

I never had any further dealings with the Field Marshal after I departed ICM for Paramount in the early ‘80s, but I was always aware of what he was up to and was delighted when he hit his box- ffice gold with the Conan movies. He was truly an American original and a unique talent from one of Hollywood’s golden creative periods.

*I lost touch with Darrell around the time Milius hit it big with Conan. Darrell’s ex-wife, Milius’ assistant, was named Carolyn McCoy and they met in their native West Virginia. Carolyn was a descendant of the real McCoys, of Hatfields and McCoys fame. “Someday,” Darrell used to say, “I’d like to tell the real story of the famous feud.”

Cut to 30 years later as I sat down to watch the opening credits of the much-heralded History Channel Hatfields & McCoys miniseries starring Kevin Costner and the gone-too-soon Bill Paxton. I reacted like Ray Liotta in the shower in Goodfellas after hearing about the Lufthansa heist when I saw in the producers credits the following name: Darrell Fetty.

By Michael Biehn and Jimi Anderson